Revenue recognition for SaaS companies depends on the pricing structure – whether customers are billed one-time, monthly, or yearly. Below we walk through different examples to help you get this right for your business.

By subscribing you agree to receive the Paddle newsletter. Unsubscribe at any time.

Picture this. You’ve just landed the biggest customer in your SaaS company’s history, adding tens of thousands of dollars to your income in a single sale.

After the cash lands in your account (and after you’ve cleaned up from the inevitable champagne-and-pizza party), you’ll no doubt want to update your accounts to reflect your newfound revenue.

Cash isn’t revenue. Even though the money might be in the bank, you can’t count it as revenue until you’ve earned it. Treating cash and revenue the same can be a fatal mistake for any business, whether it is a large, public company selling software or a local private company selling groceries.

So how do you know when to record your revenue, then, if it’s different for every business? To help you out with this financial reporting issue, we’ve put together some revenue recognition examples that show how revenue should be realized for businesses of all kinds.

Before we get into the examples, though, let’s go over what revenue recognition is and the difference between revenue and cash.

Revenue recognition is a generally accepted accounting principle (GAAP) that determines the process and timing by which revenue is recorded and recognized as an item in the financial statements. The revenue recognition principle states that revenue should only be realized once the goods or services being purchased have been delivered.

The most important thing to realize here, particularly for SaaS companies, is that cash isn’t revenue. We explain the difference in more detail in this post, but in general, no matter when a customer's cash arrives in your bank account, you don’t count it as revenue until you have delivered the product or service that it paid for.

The remaining balance should sit in your accounts as deferred revenue until you recognize it since customers can ask for your cashback at any time if you haven’t yet delivered the service (and you’re under obligation to refund them if they ask!).

For most companies—retail stores, for example—this is a subtle difference since the product is delivered as soon as the customer pays for it. But for SaaS and other business types, knowing when to record revenue is more difficult.

For most companies—retail stores for example—this is a subtle difference, since the product is delivered as soon as the customer pays for it. But for SaaS and other business types, knowing when to record revenue is more difficult.

So if you don’t record the revenue when the cash hits your bank account, when do you record it?

Revenue recognition depends on the timing and sequencing of the two main events that make up any transaction:

Both events are independent. Retail stores, for example, handle payment and product delivery simultaneously, but for many businesses, one event frequently occurs before the other.

Let’s take a look at the three different situations in more detail.

This is the simplest example of revenue recognition—you deliver the product or service immediately upon purchase, and you record the revenue immediately.

Revenue for one-time purchases should be recognized immediately.

This is most common with one-time purchases, like buying groceries or one-time software packages. Because the customer takes possession of the product immediately, revenue can be realized on your income statement in the same accounting period as payment was received.

It’s also common practice for companies to wait to record revenue until they deliver the product or service to customers. This should be familiar to most SaaS and subscription-based businesses—the customer pays upfront for a fixed period (usually a month or a year), and the service is delivered over that time period.

Even though the booking for the entire year is received upfront, revenue is recognized equally across the 12-month period.

If you get paid to provide a service for a month or a year, but you receive the money immediately, that payment should be gradually recognized as revenue. Each month that you provide the service for the prescribed time means recognizing an equal portion of that income until the service delivery period is complete.

Last but not least, revenue can also be recorded after delivery of the product or service but before payment is received.

Companies don’t need to wait until payment is collected to record it as revenue. This is a key concept in accrual accounting and usually applies to service-based businesses like consultancies. A service performed in March, for example, should be realized on March financial statements, even if a client pays for said service in May.

We get it—wrapping your head around all of this can be confusing. The easiest way to explain when you should recognize revenue in your own business is by seeing it in action, so let’s look at a few revenue recognition examples.

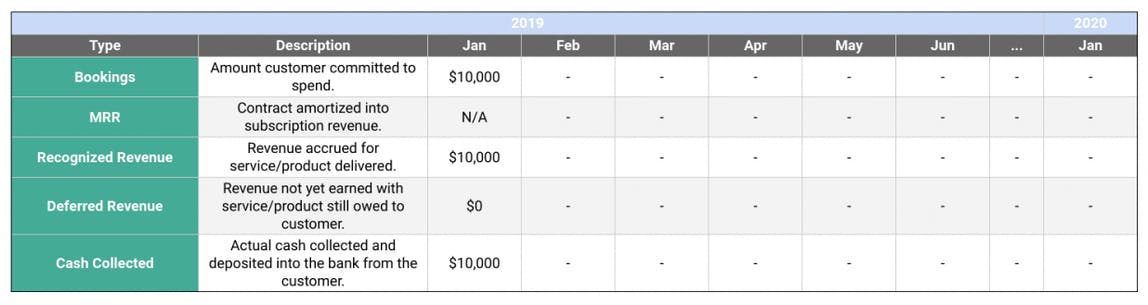

Meet Company A, a software company selling an on-prem CRM package for enterprise customers. Instead of running a SaaS product, Company A delivers their software the traditional way - a one-time software package, installed on local hardware run by the customer.

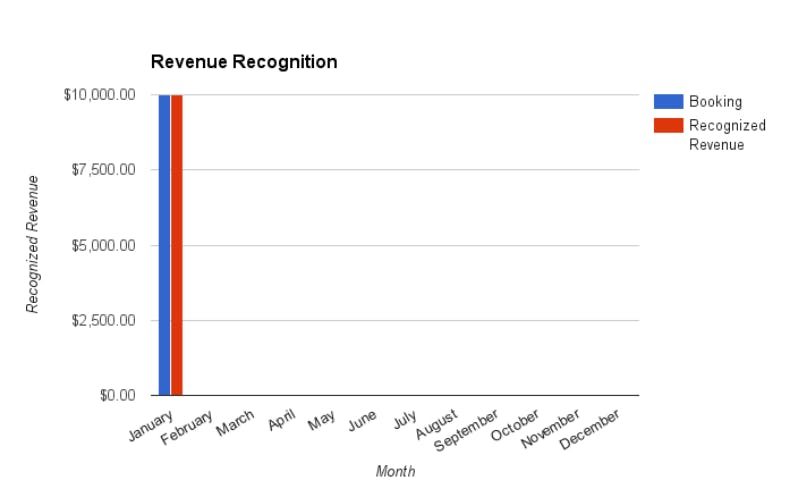

Say Company A releases a new version in January, and the new version costs $10,000 upfront. If a customer purchases and receives the software in January, the company can book the sale and recognize all $10k of the revenue in the same month.

This is the simplest example of revenue recognition. Because the customer takes possession of the software immediately and runs it on their own hardware, the seller can recognize the revenue immediately. Retailers like grocery stores work the same way—revenue is recognized upon delivery, when customers buy their groceries.

Even with this straightforward example, though, it’s still important to recognize the difference between cash and revenue. That difference becomes more apparent in our next example.

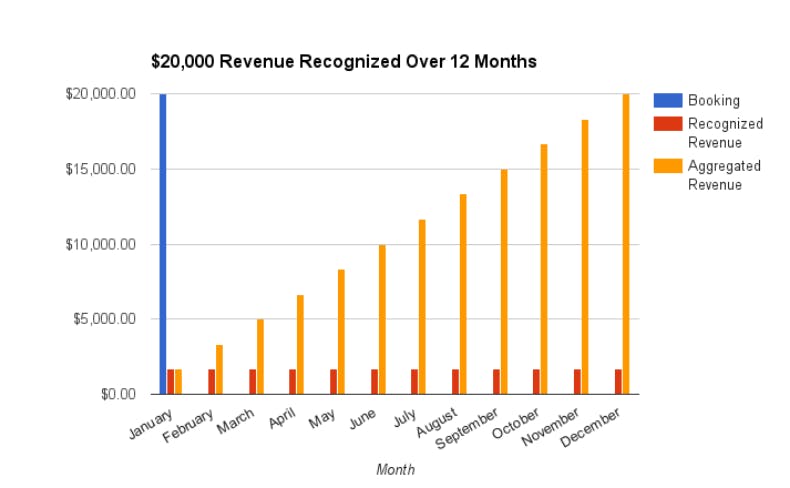

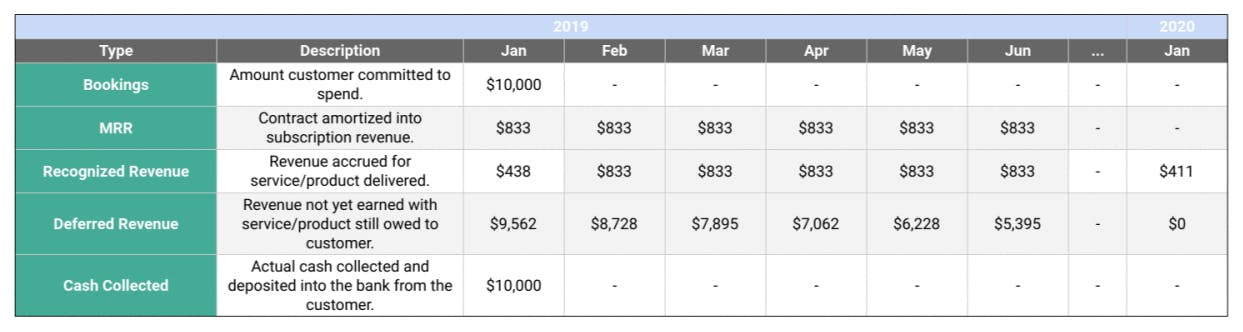

Let’s move on to Company B, another CRM software provider who develops a SaaS product. Instead of a one-time charge like Company A, though, Company B charges a $10,000 subscription fee each year for access to their service, and most customers pay for the entire year up front.

Take a look at what happens when a customer signs up for one year on January 16th:

The difference with subscriptions? Company B still has to earn their revenue, even though the customer has already paid for the whole year in advance. Delivery of the service spans the whole year—this means recognizing revenue on a straight-line basis where revenue recognition occurs monthly and the rest is deferred revenue, even though Company B's already seeing an improvement in their cash flow.

The problem with SaaS is that the subscription business model falls between the gaps of GAAP. There aren’t any specific revenue recognition standards for SaaS businesses. This is where a number of SaaS companies trip up—since there aren’t any accounting standards, they fail to realize that they have to recognize the revenue for a service incrementally throughout the time window for that service. If you recognize all the revenue upfront and then spend the cash, if a customer comes to you asking for their money back, you’ll likely find yourself up the proverbial creek without a paddle.

Now, let’s jump out of the software world. Company C sells appliances, and their lack of showroom space means customers often purchase dishwashers, fridges, and other items without being able to accept the products on the spot. Instead, they schedule delivery and installation for a later date.

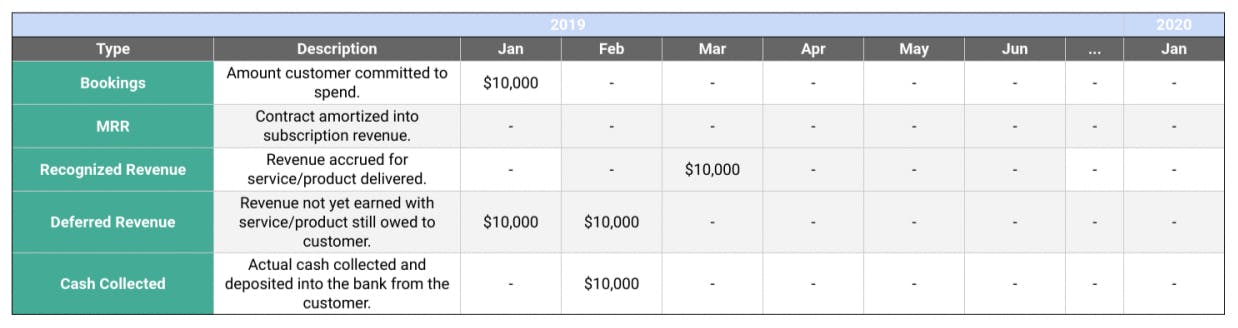

Say Company C sells an appliance package to a customer on January 16th for $10,000. The customer pays for the appliances on February 10th, but the appliances aren’t delivered until March 3rd. Let’s see how it plays out (you can ignore MRR since renting appliances isn’t common):

Company C should recognize their revenue when items are delivered to the customer, even if paid for in the weeks or months prior. In this specific example, Company C should record the revenue in March—since that’s when the products were delivered—even though the sale was booked in January and paid for in February.

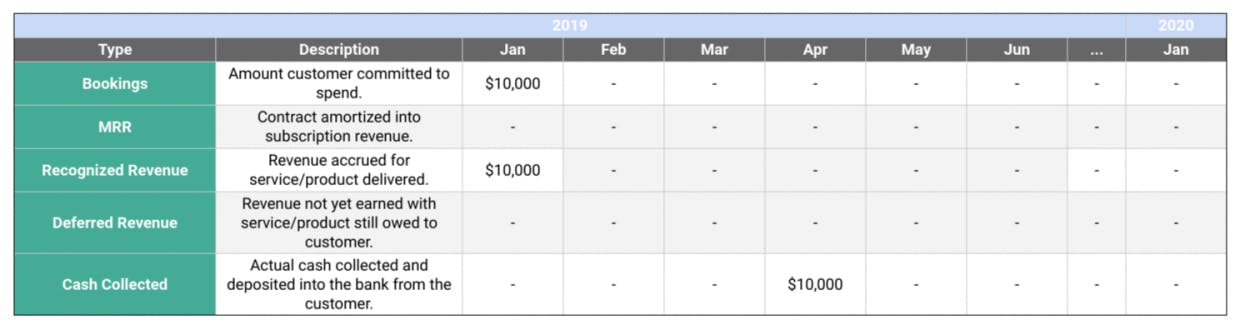

Our final example comes from the consulting world. Company D is a marketing firm that provides digital marketing solutions to growing startups. Say Company D provides $10,000 in marketing services to one of its clients in January, but the client doesn’t pay for those services until April:

Revenue recognition for service-based work like consulting happens at the time of consulting (when revenue was realized and earned) even if the client pays at a later time. This means Company D should recognize their client revenue in January, even though the cash for those services wasn’t received until April.