Entrepreneurship is rooted in the entrepreneur’s identifying, seizing, and aggressively taking advantage of an opportunity—and innovation is often at the core of this response. The opportunities for social innovation are abundant and the range is vast: even in market sectors in which there are many established providers, social impact leaders are often able to uncover previously unimagined opportunities and disrupt long-standing equilibriums—whether with a new product or service, or with an adaptation of an existing product or service (via identification of, for example, a new geography, customer, or delivery mechanism). And for social impact leaders assessing the quantity and quality of opportunities, the first step is to understand the market in which they wish to innovate.

Organizations sharing a single market may compete for two key resources . . .

Donors

There is considerable competition for support from foundations, corporations, and individual donors, with many organizations vying for grants. Investing in fundraising capacity and talent is seen as a strategic response to the struggle for donations, and for salaries for proven development professionals to continue to rise. Still, competition for funding is driven by an odd combination of performance, reputation, and personal relationships. Because funding decisions are often opaque and market signals unclear, managing competitive pressures in the funding domain is especially challenging.

All organizations, even nonprofits, operate in the context of markets. At the highest level, a “market” is the summation of the various providers offering the same product or service, usually within a finite set bound by a specific customer or geography. For example, the afterschool elementary education market for a particular city would comprise all the organizations providing after-school services to elementary school children. However, organizations operate simultaneously in different layers of markets, and the resulting list of providers that will share that space is directly determined by the defining criteria of the market. Thus, providers in the after-school elementary education market might be further segmented into smaller markets by limiting the geography, the organizational type (faith-based, public, private, nonprofit), or the specific services offered. Each of these filters will yield a slightly different solution set in which an organization can assess both its competitive advantage and its ability to maximize the opportunity for innovation.

Providers within a defined market may be formally competitive or may see themselves as more collaborative. However, in most cases, even in markets of exclusively nonprofit organizations, the providers within a single market compete for donor support and client fees. For example, nonprofit programs providing adult literacy training in a particular city make up the adult literacy market. These organizations compete, at the very least, for limited funding, and also to some extent for clients and access to other resources. While the desire to put other organizations out of business may not drive the competition within this market, the other organizations nonetheless constitute the competitive landscape.

Finally, in some cases a nonprofit may be working in a space that has a significant cap on its resource pool. Understanding the limitations and potential expandability of that pool is an important factor in understanding one’s potential placement in a market.

Competitive analysis is a tool that social impact leaders can use repeatedly throughout the life of an organization. In the start-up phase, competitive analysis is fundamental for assessing the quality of an innovation and the risk inherent in its pursuit. As the organization grows, accurate competitive analysis provides dynamic feedback about strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, thereby guiding the formulation of strategy and providing insight into how and where social impact leaders should focus limited resources.

Many popular tools are available for competitive analysis at various stages in an organization’s growth, depending on the question the entrepreneur seeks to answer. Among the more well known are SWOT, the six forces model, and Michael Porter’s four corners model. Each tool provides a specific lens through which a social impact leader can critically assess the organization, its position relative to competition, and its opportunities for innovation and growth. But our goal here is not to provide a comprehensive diagnostic tool kit for all types of competitive analysis. Rather, we show how one simple but useful tool enables social leaders to conduct a quick, robust, and insightful analysis of opportunity and competition, and from there to maximize social innovation and impact.

As social impact leaders attempt to home in on a perceived opportunity and articulate an innovation with potential for meaningful impact, the process of competitive analysis provides essential feedback on both the quality of the innovation and the risk involved in its pursuit. At the most basic level, the competitive analysis functions as an inventory of other organizations providing the same or similar products or services, and often immediately signals the magnitude of the proposed innovation. More-detailed competitive analysis enables the leader to highlight specific competitors and illustrate what differentiates his or her organization. Clear and accurate understanding of the landscape is essential for creating a powerful organizational strategy.

Unfortunately, when compared with traditional private sector competitive analysis, competitive analysis for the social impact leader can often be more challenging. First, many problems of interest to leaders are partially addressed by multiple markets. Clean water in the developing world, for example, can be provided by drilling new wells, or via filtration systems, or through the sale of bottled water. Second, within those markets, products and services may be provided by many different types of organizations, including for-profits, nonprofits, and/or hybrid organizations. This heterogeneity can make it particularly difficult to accurately map the market. For example, an affordable housing market might include public-, nonprofit-, and private-sector providers. And the array of solutions might include low-priced renovated townhomes, small rental apartments, or shelters.

Why is it important for leaders to correctly identify the market or competitive landscape in which they will operate? First, through this exercise they can orient themselves and assess where their ideas and organizations fit relative to other providers in the space. Second, they can gain critical insight into the risks associated with pursuing an innovation or opportunity. For example, at one end of the spectrum, the social impact leader may find that there are no other organizations currently operating in the market. This strongly signals high risk. On the other hand, entering a market saturated with similar providers is also a high-risk situation. Concentrating on the traits of immediate competitors forces the social impact leader to focus intently on the response to one question: what positively differentiates my idea and/or my organization? All viable, successful, impactful organizations must differentiate themselves on at least one criterion, and to be truly innovative, they will likely differentiate on many more.

Competitive analysis is an essential tool not just for leaders seeking to position a new innovation and/or organization within the context of existing providers but also for established organizations to continually orient themselves in a changeable landscape. All of the aspects of a competitive landscape are continually in flux: organizations evolve internally, developing both core strengths and weaknesses; conditions change externally, yielding substantial opportunities and threats. As a result, to stay competitive organizations must conduct ongoing, dynamic assessments of these conditions and, through those evaluations, test ideas about future growth.

Competitive analysis can also reveal possible opportunities for collaboration. Some organizations may appear to be competitors on the surface but, upon further investigation, turn into potential partners, assuming there are significant differences in terms of the population served, the program services offered, or the geography covered. In the nonprofit sector, given the immensity of social problems and the long list of potential clients, uncovering potential collaborations and fruitful partnerships can be helpful.

While our focus here is on competitive positioning, we do not want to foreclose the possibility of substituting collaboration for competition when collaboration is both possible and advantageous. Indeed, collaboration can turn out to be an organization’s competitive advantage, and how the partnerships are used, its innovation. Opportunities for collaboration generally depend on some overlap in organizational mission and focus, and knowing what others offer can thus be a first step in mapping both competitors and potential collaborators. Collaborations can be difficult to define and manage, however, and sometimes a competitive lens is the appropriate one, even if this proves culturally challenging to nonprofit leaders.

Next, we offer systematic advice for understanding and managing competition.

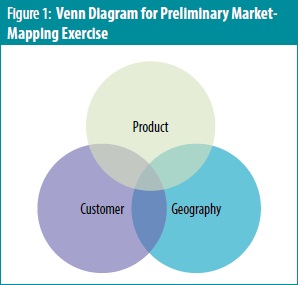

All social impact leaders should build a comprehensive map of the overarching competitive landscape. This rapid exercise should yield a picture of many relatively diverse organizations. The benefit of developing the map is to establish a rough boundary for the market in which the organization will operate. At this level, the market may be quite heterogeneous, with limited overlap among the organization’s geography, customer, and/or products; however, the exercise is particularly useful for quick observation of industry trends and, with limited effort, can shed light on the positioning of any organization—whether new or old.

When constructing a broad competitive landscape, the most important differentiating criterion to consider is the product or service the organization provides. Ask yourself, “Who else is providing the same product or service?” Sometimes the answer is “dozens of organizations spread over diverse geographies.” In that case, the leader should apply other relevant filters, such as customer and/or geography, to improve the focus. In other situations, when the product or service is very new, only a handful of other organizations worldwide may be offering the same thing. In this case, additional filters limit the solution set too much and therefore should be temporarily ignored.

When the set yielded by the first question is very large, the next two important filters are customer and geography. Specifically: Who is providing the same product or service to the same customer (but potentially in different geographies)? Who is providing the same product or service in the same place (but potentially to different customers)? And who is providing the same product or service to the same people in the same place?

The goal of this filtering exercise should be to map between ten and twenty organizations that have as many as possible of these three criteria in common. The results of the inquiry would show, in a Venn diagram, as the organizations occupying the center, overlapping space (see figure 1).

While it is important for all organizations to assess their competitive markets—and their niches within those markets—periodically, nonprofits are very often drawn to the task by a new program or innovation, or a significant perceived shift in the market. The preliminary market-mapping exercise is a useful tool at two different junctures. In the start-up phase, preliminary market mapping enables the social impact leader to rapidly assess the risk of entering a new market. In the ongoing/growth phase, preliminary market mapping allows the social impact leader to quickly glean industry trends that are useful for informing strategy and planning.

In the start-up phase, when the mapping exercise yields an empty set, meaning that there are no other organizations providing the same product or service, very high-risk conditions are indicated, because the market is either unproven or has proven so hostile that no organizations have survived. Sometimes preliminary market mapping yields a large solution set of providers already operating in the product or service space; this, too, is a high-risk scenario, because of the added pressure to convincingly differentiate the new idea and organization and to bolster the new organization against the advantages of established providers.

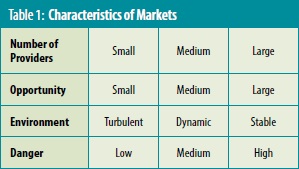

Whether the organization is new or established, one of the social impact leader’s first assessments in reviewing the preliminary market mapping data should be an evaluation of the speed of change in the market. Is the market stable, with a relatively unchanging set of organizations? Is the market dynamic, with organizations regularly entering and/or exiting the space? Is the market turbulent, with ongoing change in the number and composition of other organizations creating significant instability? By documenting the main competitors and comparing these data over a relevant time frame, leaders can quickly determine the speed of environmental change within their markets and how that will affect their entry strategies.

A second key assessment should be a measurement of risk, based on the number of current competitors in the space. In cases where preliminary mapping yields no relevant competitors, the social impact leader should be able to articulate how he or she will respond to that particular high-risk condition. Why would a market not have any current operators? There are several potential explanations for an empty market, including: there is no perceived opportunity; unknown external forces have eliminated previous organizations attempting to harness the opportunity; the market is so turbulent that all previous providers have exited; the opportunity is so new that no other organizations have attempted to address it. An empty market should be a warning sign, and leaders should undertake extensive due diligence to uncover the reasons for the lack of other providers. It may simply be that this is the first opportunity to implement this innovation, but often an empty market signals a high risk of failure.

Preliminary market mapping may also reveal a saturated market, in which dozens of existing organizations are providing (or attempting to provide) a similar product or service. This scenario is also very risky, because evidence of a large number of stable providers means competition will be strong, and existing providers are often able to leverage to block the threat of new entrants. In this situation, the leader will have to respond to concerns about the threat of existing providers, who usually have more resources available to “steal” or replicate a promising idea.

In general, social impact leaders should look for markets where the trade-offs between risk and opportunity are balanced. Usually these markets have dynamic conditions, with a small number of diverse players who are successfully mitigating risks while taking advantage of latent opportunities (see table 1).

Preliminary market mapping allows the social impact leader to quickly assess the potential riskiness of entering a new market. It also crafts a landscape from which it is possible to observe and track high-level industry trends. However, this perspective is usually too broad to provide relevant details about the risks and opportunities a single organization faces. In order to answer these questions, most social impact leaders will carve out a subset of the broader market and focus on a smaller number of organizations that can be compared along a specially selected, more relevant set of criteria.

Having constructed a broad overview of the market, the social impact leader will next want to undertake detailed mapping by applying more specialized filters to deliberately sort organizations and clearly demonstrate differentiation. Detailed market mapping engages three key questions: (1) What characteristics describe the organization but not its competitors? (2) What characteristics describe the competitors but not the organization? (3) Which of these answers matter?

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

From the preliminary mapping, the leader should have a list of about twenty organizations that make up the overall market. The next step is to hone that list down to a smaller subset of approximately five to seven organizations that have sufficiently relevant, similar characteristics to indicate the direct competitive landscape.

Through this exercise, the leader presents his or her niche or difference in the context of immediate competitors, and must be able to visually demonstrate how the innovation and organization stand apart from others in the same space. At the same time, the organizations must have sufficient overlapping characteristics to show that they are in the same market. The selection of these characteristics is key to clearly and persuasively demonstrating how each organization relates to the other. This information forms a snapshot—the competitive matrix of the organization.

Selecting the best criteria to define the immediate competitive landscape and construct a competitive matrix is not a straightforward exercise. In theory, a leader could select from an almost infinite number of characteristics. On one level, the process of defining a market is highly subjective, as the leader has flexibility in selecting the defining criteria. On the other hand, incorrect selection of the criteria not only yields flawed results but also undermines the credibility of the proposition by appearing to bias the results.

In addition, the criteria selected will directly affect both the size and the composition of the resulting set. Specifically, criteria that are too broad will yield an overly large market with too many undifferentiated competitors, whereas criteria that are too narrow will yield an overly small market with too few competitors. Likewise, criteria that are too broad will not usefully distinguish the niche, while criteria that are too narrow will not set it in the context of relevant substitutes. The social impact leader must find a delicate balance in which the selected criteria are sufficiently informative to support meaningful analysis without contriving the results. In sum, the leader should select criteria that present a robust and seemingly unbiased perspective on the position of the innovation and the organization while also focusing on criteria that clearly demonstrate the strengths and differentiators.

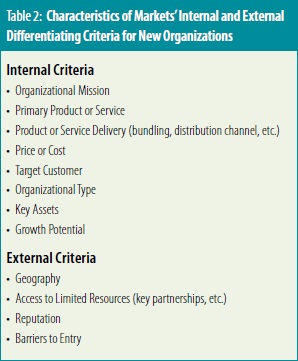

How can a social impact leader select the best characteristics with which to construct the direct competitive landscape? To start, the leader should brainstorm a list of all of the characteristics that he or she feels distinguish the organization and the idea. These characteristics may be internal to the organization, such as the new product/service offered or the mission, or they may be external advantages, such as a key strategic relationship or access to a new geographical area (see table 2).

Most organizations tend to focus heavily on the differentiating criteria of the new product or service. However, sometimes that perspective can be too narrow and may overlook important differentiators that are independent of the new product or service. For example, what is the organization’s mission? Does it differentiate itself with B Corp certification or other commitments that set it apart from other providers in the space? Differentiation can take many forms, and a leader needs to explore them all.

Above all, the social impact leader should select characteristics that highlight the proposed innovation. For example, is the product or service entirely new or the provision of an existing product or service to a new customer? Is it a new distribution channel or a new combination of services? Is this the first time a nonprofit organization is providing the service? Is this the first time the product or service is being offered to a new target customer? Is the product or service being offered at a new, lower price?

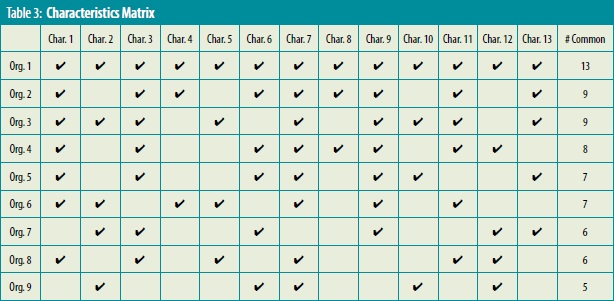

With the initial brainstorm list done, the social impact leader should begin to sort the characteristics in order of importance. With the list honed down to no more than twenty defining characteristics, the leader should then compare those characteristics to the ten organizations identified in the preliminary market mapping and consider which of those organizations share the greatest number of characteristics with the new organization. Generally, as one applies more characteristics to the filter, the number of organizations with common characteristics can be reduced (see table 3).

Ultimately, the social impact leader should narrow the list to the top five to seven organizations with the most relevant traits in common. Sometimes this set is obvious, but other times there is more art involved in selecting the right list. For example, many leaders focus too heavily on organizations that share the same geography, when it may be more relevant to include organizations with a similar product or service in another geography.

In reality, the list of the most important differentiating characteristics is a best guess, particularly for start-up organizations, and the social impact leader will have to hone the list over time. Not only will an organization evolve and change its position in the market but also many leaders may not initially fully understand the strengths and differentiating characteristics of their own innovations. Only after launching an organization and interpreting significant feedback from the customer will the leader be able to refine his or her list of criteria and competitors. As a result, social impact leaders should expect to continually refine the list of criteria that distinguish their organizations as well as the list of direct competitors.

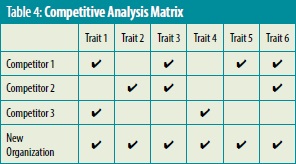

Once the leader has identified the three to five organizations and five to seven characteristics that best compare and contrast with his or her organization, the next step is to assemble that information into a useful visual snapshot—the competitive analysis matrix.

The competitive analysis matrix is a simple tool that conveys an instant snapshot of how an organization is positioned relative to its immediate competitors. The format of the matrix is straightforward, with a list of the three to five most relevant competitors on the vertical axis and a list of the five to seven key comparative traits along the horizontal one. For each trait of the organization, a check is entered in the box, creating a view of the organization’s key distinguishing characteristics. The ideal comparative analysis matrix demonstrates sufficient overlap to convincingly show that the organizations are within a similar market while also clearly illustrating the strength and competitive advantage of the new organization (see table 4).

Blue Avocado is a social purpose business that launched a reusable shopping bag system targeted toward women who want to reduce their carbon footprint without sacrificing convenience or style. At the highest level, the space in which Blue Avocado was launching was the “reusable shopping bag” market; however, this framing is too broad for a relevant competitive analysis and does not usefully reflect the niche in which Blue Avocado operates. As a result, the founders opted to reframe their market with narrower criteria, selecting the following characteristics with which to compare their innovation: whether the bag was part of an integrated system; the stylishness of the product; the degrees of functionality and portability; and price. From here, the founders were able to shrink their competitive analysis to a subset of four key competitors and five distinguishing criteria (see table 5).

From this competitive analysis, we can see that, though several of the competitive products share overlapping traits with the Blue Avocado system, Blue Avocado is the only one to have all the characteristics. This convincingly shows how the product is similar to others in the market while also demonstrating what makes it different. At the same time, the inclusion of price in the assessment indicates that Blue Avocado is pricing its product substantially above that of its nearest competitor. A quick glance at Blue Avocado’s competitive matrix raises the immediate question of whether the combination of these specific traits will merit a more than 30 percent increase in price for the product. Will customers value this combination that much? By positioning their competitive analysis in this way, the Blue Avocado founders are arguing that, yes, their price increase is justified.

In fact, after two years in the market, they discovered that the price point of $50 was too high to achieve the scale they desired, so they introduced additional product lines at lower price points. This discovery was an important insight into their innovation, resulting in product modifications that strengthened their business and enabled them to reach more people. The risk associated with their high price point was clearly demonstrated in the competitive analysis, and fortunately, because they were aware of the potential for challenges in that area, the founders were able to respond quickly with alternative products.

There is no single correct competitive analysis matrix. In fact, the social impact leader may wish to construct multiple, varied competitive analysis matrices for different audiences. For example, one matrix may focus predominantly on the product space, illustrating how the new product is differentiated from other similar ones. Another matrix may focus on a common geography, and the compared organizations may not have much overlap on product or service but may all be serving the same or similar customers within a community.

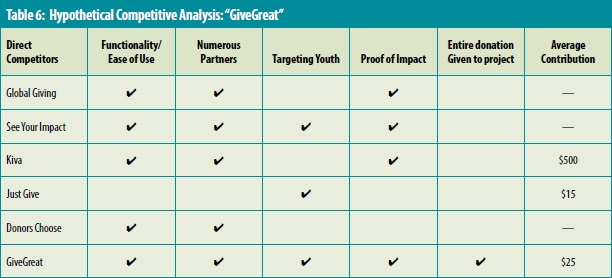

If a social impact leader wanted to enter the online-giving space with a new service called, say, GiveGreat, a competitive analysis would reveal a crowded field, but one where a focus on impact measurement, working with young donors and seeking small gifts, might find a place. Of course, there would be some challenges to constructing the matrix, since some of the information about competitors might be proprietary and hard to obtain. But an initial mapping would still help to define the lay of the land and the possibility for a successful new entry.

Again, the choice of the key characteristics will prove critical. If GiveGreat gets this wrong, the entire exercise will be compromised. Thus, if it turns out that administrative overhead is a critical consideration for donors looking at online-giving options, omitting this characteristic from the competitive analysis will be a serious mistake and lead to false conclusions about the merits of the innovation or enterprise. Taking time to get the characteristics right may involve talking to users and doing market research before setting the terms of the competitive analysis. In this hypothetical case, the market looks primed for a youth-oriented and small-scale giving option (see table 6).

The most important function of the competitive matrix is to quickly convey how the new organization fits into its market and distinguishes itself. All organizations (including nonprofits) must be able to demonstrate how they are different and better than their competition. At the same time, as described earlier, the degree of differentiation is also an important indicator of risk: organizations that are not clearly and convincingly differentiated are at higher risk of failure.

Social impact leaders should always use competitive analysis to inform the honing and development of their innovations. For each instance, when a direct competitor possesses a characteristic that the organization in question does not, leaders should carefully evaluate the importance of that distinction. Specifically, they should ask themselves, “Is that characteristic a strategic advantage for the other organization?” If it is not, leaders should be prepared to articulate why. If it is, leaders must begin to plan how they will address that distinction. Does the leader’s organization have other advantages that neutralize this threat or should a similar advantage be sought through either adoption or collaboration?

Similarly, social impact leaders should also be alert to instances in which all their direct competitors have a similar characteristic that their organization lacks. For example, if all of the competitors are using a similar distribution strategy for a product or service, this may indicate that this strategy is the only viable option, for pricing, regulatory, or other reasons. Leaders wishing to deploy entirely unique strategies should be sure to understand clearly why all the other competitors share a common approach and how deviating from the group may or may not be helpful. In the case of Blue Avocado, the competitive analysis underscored that its price point was significantly higher than that of other immediate competitors, and that it was deviating from the general trend of the group. It was hoping to prove that its innovation—combining the traits of a bag system with high style, functionality, and portability—was both substantial and valued enough by customers to warrant such a price increase. In the end, the analysis demonstrated that while the innovation was valued sufficiently by some customers, this was not enough on which to build a sustainable business model—so Blue Avocado quickly adapted and created new products at lower price points.

In some cases, an organization can immediately incorporate the insights gleaned from competitive analysis into the proposed product or service. At other times, as in the case of Blue Avocado, an organization must carefully note potential risks or modifications and then activate the product or service only if the market affirms the hypothesis. Sometimes, a leader may find it difficult or impossible to adapt the innovation, even though the competitive analysis clearly demonstrates the need for it. For example, competitive analysis may clearly indicate the benefit of a key partnership or financial investment, but due to multiple potential constraints (for example, being too small, not having enough money, and so on), the leader may be unable to incorporate the new ideas into the original innovation. Here is where competitive analysis begins to inform competitive strategy: the leader must determine whether it will be most advantageous to function competitively or collaboratively with the other organizations in the competitive landscape and how to use competition and alliances as complements and substitutes to the innovation.

Competitive analysis has three primary objectives. The first is to gauge the risk associated with conditions in the current market and the likelihood of success. The second is to uncover important insights into the quality and viability of an organization’s innovation(s). The third is to make use of the conclusions derived from the first two to develop an organizational strategy that maximizes impact. Other, secondary insights are often derived from competitive analysis, including industry trends from preliminary market mapping, clear identification and articulation of the organization’s differentiation and competitive advantage, and a detailed mapping of the organization’s position relative to its immediate competition.

Social impact can no longer be pursued without knowledge of competitors and what they offer. Organizations must understand the competitive environment as a first step in building, positioning, and growing in the turbulent waters of social innovation and impact.